|

|

|

|

|

|

.

.

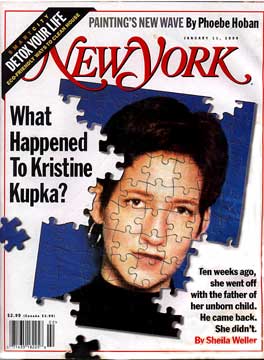

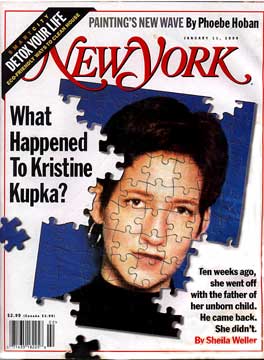

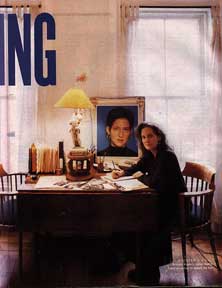

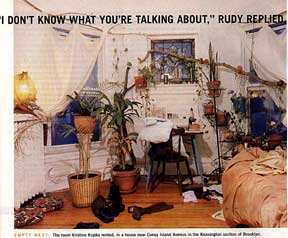

She was a romantic-you could see it in her room: handmade muslin drapes looped through dogwood boughs, low tables bearing plants, vases, goblets. A shawl-draped dresser displaying a tin Barbie box, pictures of herself as a child in Wisconsin and of her sister Kathy's adorable 2-year-old son, named Marshall, after Thurgood Marshall. The books on her shelves (Voices of Freedom: An Oral History of the Civil Rights Movement, The Philosophy of Right and Wrong, Development and Dependency) advertised a feisty, cerebral idealism. And on the floor near a stack of CDs (Jamiroquai, Liz Phair, Jeff Buckley, the Fugees) were more books, including a dog-eared copy of Two of Us Make a World: The Single Mother's Guide to Pregnancy, Childbirth and the First Year. She was five months pregnant; and though the baby was unplanned and she was adamantly pro-choice (after vegetarianism, reproductive freedom was the cause she fought for most fiercely), she never considered abortion. She was thrilled about having this child, and while her friends had no doubt she could handle single-motherhood ("Kristine is the most competent person I know," says Denise Lilien, her girlhood friend from Madison, Wisconsin), they had worried about her involvement with the baby's father. She had detailed to at least eight confidants every twist and turn in her strange, sporadic five-month relationship with her former Baruch College science instructor and had shared key parts of the story with several others. And so when, shortly after noon on Saturday, October 24, Kristine Kupka, 28, left her room with little more than the clothes on her back and didn't return, her disappearance led those who knew her to fear the worst.

Kristine was a passionate, opinionated person with a strong circle of friends and clear, close-at-hand goals. A college philosophy major two months from graduation, with a 3.97 average, she planned to go to law school and specialize in women's issues. She had a job waitressing at the Caribbean restaurant Negril, near Chelsea Piers, that she would not have abandoned. And she was happy; to those who knew her well, suicide was unthinkable.

Indeed, her life seemed as disciplined and spirited as her room in the wide-porched house near Coney Island Avenue, in a hidden pocket of Brooklyn called Kensington. Deeming Park Slope too expensive, Kristine, who had also lived in the East Village, and TriBeCa, rented two floors of this house for $2,200 a month from a Turkish family. Then she shrewdly sublet the extra bedrooms, creating a kind of MTV’s Real World of frugal young urbanites: an extravagantly tatooed club bouncer, a New York Times cyber-journalist, a hotel trainee, and two college students.

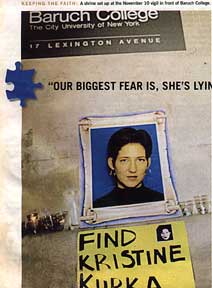

Within a week, there were news reports of her disappearance

(PREGNANT HONOR STUDENT IS MISSING; SIS FEARS PREGNANT BARUCH COED WHO VANISHED

IS DEAD), and on November 10, her friends held a vigil. Outside Baruch’s

main building at Lexington Avenue and 23rd Street, they embraced, cupped votive

candles, help up signs expressing their fear and outrage (KRISTINE KUPKA:

MISSING 17 DAYS; 17 DAYS TOO LONG) Kristine’s sister, Kathy, heartbroken,

and hoarse, was given a bouquet, and a plate was passed to collect reward

money.

Then weeks went by without a breakthrough. As

the November wind loosened the flyers (please help me find my 5-months pregnant

sister) from the maple trees, the candle-clutching group that assembled in

front of Kristineís house for a second vigil was smaller, and the TV

crews failed to materialize. A mere $5,000 had been raised to induce anyone

with information to come forward. (It has since been doubled, with a donation

from Baurch’s alumni association.) Kathy Kupka had taken on the drained

aspect of Dorothea Lange’s dust-bowl mother. Desperate to believe Kristine

might still be alive, she had spent a recent day and night in New Jersey,

futilely following a telephone tipster who promised to lead her to her sister.

That outing had underscored her hellish limbo: Should she hope, or grieve?

Use common sense, or take leaps of faith? Speak in the present or past tense?

Frustration

of a different sort plagues authorities in missing-persons cases. Without

a body, it is extremely hard to prove that a crime has even been committed.

Prime examples are the recent indictment of grifters Kenneth and Sante Kimes

for the murder of heiress Irene Silverman, and the indictment, in November

1997, of prominent Delaware attorney Thomas Capano for the June 1996 murder

of governor’s assistant Anne Marie Fahey. In both cases, police had early

circumstantial evidence that pointed to the suspects. But the absence of a

body made securing indictments extremely arduous. In the Kupka case, the police

still aren’t certain that a homicide has been committed.

Frustration

of a different sort plagues authorities in missing-persons cases. Without

a body, it is extremely hard to prove that a crime has even been committed.

Prime examples are the recent indictment of grifters Kenneth and Sante Kimes

for the murder of heiress Irene Silverman, and the indictment, in November

1997, of prominent Delaware attorney Thomas Capano for the June 1996 murder

of governor’s assistant Anne Marie Fahey. In both cases, police had early

circumstantial evidence that pointed to the suspects. But the absence of a

body made securing indictments extremely arduous. In the Kupka case, the police

still aren’t certain that a homicide has been committed.

By early December, the number of detectives working on the

case had shrunk to four; by mid-December, to just two. Today, ten and a half

weeks after Kristine’s disappearance, the identity of the Baruch College

teacher who left with her that morning is still being kept secret by the nervous

college and the proprietary Police Department. Kristine Kupka's family and

friends, convinced her fate lies in his hands, believe it is time to change

that.

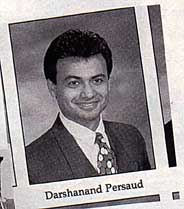

The man who accompanied Kristine on her October 24 outing is

Darshanand Persaud; most people call him Rudy. Persaud is a respectable young

Indo-Guyanese-American. A 1995 graduate of Baruch, a Manhattan-based branch

of CUNY, he was a quality-control chemist testing glue products at Basic Adhesives,

in Brooklyn, and an adjunct lab instructor at his alma mater. He currently

attends the New Jersey Dental School in Newark, making a cumbersome commute

(subway to path train to school bus) to get there each morning. He is now

married to an accountant in the Dreyfus Corporation’s Park Avenue office;

the couple lives with his parents in a neat house in a rundown section of

Brooklyn. He’s the family’’s only son; the oldest of his three

sisters is a physician.

Miguel Santos, the lecturing professor for Introduction to

Environmental Sciences, whose lab sections Persaud taught found him "a

very pleasant, cordial, nice person, knowledgeable in science and a good teacher."

Students characterized him as handsome, sometimes polite, sometimes angry

and moody. He was decorous; he had refrained from dating Kristine, his student,

until he had filed her course grade. It was Kristine—with her long, black

clothes, bright-red hair, extra-strength opinions—who had flirted with

him.

When Kristineís classmate Anthon Grant, a 26-year-old

Trinidadian who had

befriended Persaud on the basis of their mutual interest in computers, and

shared Caribbean background, told him last May that he thought Kristine had

a crush on him, "Rudy said, ‘come ahhhhn....’ "

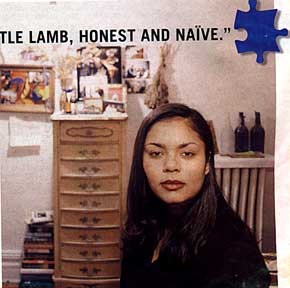

Kristine found Persaud's shyness charming. "She thought of him as this

gentle-lamb sort of guy, honest and naive," says Michael Legatt, a member

with Kristine’s of Baruch’s Philosophy Club. Indeed, Persaud’s

clean-cut looks and slight awkwardness led her to compare him, to several

friends, to a "newborn baby."

Where Kristine saw guilelessness, Anthon Grant saw calculation.

"Rudy was very GQ-ish. He never had a bad-hair day. He seemed like someone

who had his own agenda—like his main goal was getting ahead in life,

like he didn’t want to be where he was, that’s for sure. He would

walk into class late, in a trench coat, like he’d just come from someplace

important." He was "Mr. Persaud" to his students who were mainly

his age, and when the class first overheard Dr. Santos address him informally,

"we looked at each other, like,’Rudy!" Grant says, laughing.

It seemed too goofy a name for Persaud.

Though few at Baruch knew, Persaud was that rare thing in India, rarer in

Guyana, and rarer still in New York: a true Brahmin. And a Brahmin with a

pandit (a priest) for a father. Kristine Kupka was a kind of reverse Rudy

Persaud. They represented two different versions of the romance of migrating

to New York City—colliding examples of the postmodern melting pot. He

moved here as part of an esteemed ethnic family, part of an ambitious community

of immigrants who had a literal caste system. She moved to New York in a quasi-bohemian

fashion: a white, blue-eyed Midwesterner drawn to milieus in which she was

the racial minority. Baruch has a predominantly non-white student body; and

Negril, where she worked, has a largely Caribbean clientele. Many of the men

she had dated were black. Anthon Grant says, "I don’t think Kristine

saw color."

Where Persaud maintained the formality and reserve of the Anglo-Indian

culture, Kristine, a graduate of the Forum, a modified reincarnation of Werner

Erhard’s EST seminars, "revealed herself," Denise Lilien says.

"She didn’t hold back; she really developed intimacies. She was

willing to put so much on the table so quickly. She was ‘This is who

I am; this is what I can give.’ That’s how she was with men, too.

It was often too much. It could be overwhelming."

On October 24, a little past 11 a.m., Persaud pushed the buzzer at Kristine’s

house. He had called the night before, she told her roommate Ozlem, a 22-year-old

Near Eastern college student (who asked New York to withhold her last name),

to tell her he had found an apartment in Queens and wanted her to see it.

But Kristine had overslept; she called out to Ozlem to let Rudy in. Ozlem

says she sensed that Rudy did not want to come upstairs. When he did, "he

was pacing around. He had his hands in his pockets like he was distressed."

Kristine came out of her bedroom in her pajamas and sat with Rudy, eating

her health-food breakfast. Ozlem then when to her room; another housemate

glimpsed Kristine, in a long black skirt and black sweater, leaving with Rudy.

That was the last time any of Kristine’s friends or family saw her. Her

last communication was a message left on Kathy’s answering machine, apparently

just before she walked out the door: "I’m going to look at Rudy’s

new apartment in Queens. I’ll call you later this afternoon. See ya."

When Kathy didn’t hear from hers sister that afternoon

or that night, she began to worry. When Ozlem called the next morning to say

Kristine had still not returned, Kathy’s worry turned to alarm and dread.

She and her husband, Kevin (he’s a parole officer, she a teacher), bundled

up their toddler, Marshall, and rushed to the 70th Precinct.

At the 70th, Kathy and Kevin were given a stock response: Because Kristine

was over 16 and under 65 years old and of sound mind and body, a missing-person

report could not yet be filed. Maybe she took a trip home to Wisconsin or

a vacation to Bermuda, it was suggested. Kristine wouldn’t do that! Kathy

protested, to no avail. It would be two days before the police called her

to take an "informational account" of Kristine’s disappearance.

The couple raced back to their Brooklyn apartment, with its pictures of Gandhi,

Martin Luther King, Frida Kahlo, and Huey Newton, to plot their next move.

Both former caseworkers and political activists, Kathy is cool and wry, and

Kevin, who is African-American, has the efficient manner of a young executive.

They immediately started making calls and designing a flyer. Kathy left a

message for her and Kristine’s mother. Ellie Bodell, 64, is as much as

freethinker as her daughters: At age 56, she became a long-distance truck

driver. She was on the road and didn’t get Kathy’s frantic message

until October 31. When she heard it, she says, "I just sat here in total

shock." Then she flew to New York.

Monday morning, October 26: Still no Kristine. Kathy and Kevin

went to Baruch. Joining them was Nick Papanikolu, a darkly handsome, quite

graduate student who had lived with Kristine for three years; since breaking

up two and a half years ago, they had been the closest of friends. Kristine’s

disappearance has since taken over Nick’s life; he dropped out of school

to search for her, and virtually lives at Kevin and Kathy’s. They tried

to get Persaud’s home address from Baruch, but a clerk in the personnel

office told them they’d need a subpoena. Through a chain of acquaintances,

they came up with an approximate address in Bushwick.

Nick and Kevin drove out to a row of attached redbricks with aluminum awnings,

gated windows and doors, shrubs, and chain-link fences. In front of one: Indian

and Guyanese flags. Its sidewalk bore a child’s worn wet-cement legend:

rudy.

Nick and Kevin waited in the car. When an older man approached the house,

they approached him. Rudy’s uncle. He had seen Rudy Saturday morning

and then not again until Sunday evening. At 5:30, a woman appeared. Rudy’s

mother. "We started hitting her with all these facts,"Kevin recalls,

"and told her we needed to question Rudy and to have him here at seven."

![]()

Nick and Kevin waited in the car. At seven, a

police van pulled up. Two officers got out, guns drawn. (the NYPD refused

to grant New York an interview with the two officers.) They ordered Nick and

Kevin out of the car and lightly frisked them. Then a young man climbed out

of the back of the police van. "He was dressed very preppy," Kevin

recalls. "Cardigan sweater, white shirt, dark dress pants, Jansport backpack."

It was Rudy. Apparently alerted by his mother that two men were harassing

the family, he had gone to the precinct and obtained a police escort.

"Where’s Kristine?" Kevin demanded.

"How should I know?" came Rudy’s flippant answer, according

to both men.

"You killed Kristine!" Nick insisted. "Where is she?"

"He said, ‘I donít know what you’re talking about,’

and ‘Why don’t you go file a missing-persons report.’"

Recalls Kevin.

Kevin asked Rudy what he and Kristine had done on Saturday,

since "you were the last one seen with her." He said that he had

dropped Kristine off two blocks from her house between 3 and 4 p.m., because

she wanted to go to the health-food store, and that that was the last time

he had seen her.

Kevin asked Rudy where he'd gone with Kristine. Rudy said they went shopping.

Kevin asked where. Rudy answered, "Some mall." Kevin and Nick kept

the questions up: Which mall? Which stores? Rudy said he had stayed in the

car while she shopped.

Five days later, when the news media were told of Kristine’s disappearance,

reporters canvassed Kristine’s neighborhood, as had the police and Nick,

Kathy, and Kevin—all asking whether anyone had seen her on Saturday.

A Laundromat owner said he’d seen her through his window, and a health-food-store

worker thought she may have seen Kristine in the store—"after dark,"

at about 7 p.m.

The health-food-store worker is now "pretty sure" the woman she

way after dark on Saturday, October 24, was not Kristine—among other

things, that woman was wearing peach-colored pants, which Kristine did not

own—but rather another customer "who looks a lot like her."

And the Laundromat owner, who says he told his original story "to try

to help," now says he does not know whether he saw Kristine on Saturday,

the 24th, or Friday, the 23rd. On November 2, Rudy Persaud sat down for police

questioning with his attorney. A police source says, of Rudy’s November

2 interview: "Did he cooperate? Yes. Did he had an airtight alibi? No."

"There’s an old movie where a guy is walking down

the street under a street-light looking at the ground. Another guy says, ‘what

are you looking for?’ The first guy says, ‘I lost my glasses.’

The second guy says, ‘Where did you lose ‘em?’ He says, ‘I

lost ‘em over there . . . but the light’s better over here.’"

Lieutenant Phillip Mahony, comading officer of NYPD’s Missing Persons

Bureau, likes telling this story. His small office is dominated by metal file

cabinets. Several drawers are marked patz and contain files relating to the

maddeningly unsolved 1979 disappearance of 6-year-old Etan Patz in SoHo. The

lost-glasses story, says Mahony, illustrates the problem with having too obvious

a suspect: He might not be the killer.

"I can tell you this, none of the four detectives on this case think

it’s open-shut," he says. "This Rudy may be the guy. You certainly

had a guy with a motive. He was the last one seen with her—you can’t

ignore that. But it still doesn’t add up. It’s no crime to be the

last person seen with somebody. It’s no crime for a married guy to get

his girlfriend pregnant. It’s a shame but not a crime. You can even say,

‘I have plenty of reason to want her gone,’ but you’re still

not gonna get an arrest on it.’ (Repeated efforts were made by New York

to contact Rudy Persaud for an interview.) Mahony says: "Our biggest

fear is, she’s lying in a ditch somewhere—the result of an accident

or random mayhem—"and we’re walking by her every day because

we’re focused on Rudy."

To this end, detectives combed the tracks of the D train, which

she took to Baruch. They choppered low over Brooklyn and Queens and took pictures.

Kristine’s family and friends have also gone searching. With the help

of ex-NYPD detective Gil Alba—a specialist in solving kidnappings by

Colombian and Dominican drug dealers—and using maps of abandoned industrial

sites, parks, wetlands, and isolated land near bridges (all places where bodies

tend to be buried) they have gone out in small parties several times a week,

talking to park personnel, harbor partolmen, dog walkers, joggers, and vagrants.

But these searches for Kristine have been futile.

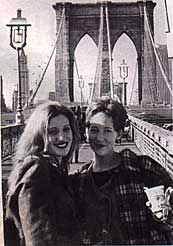

Denise Lilien, now a business consultant, first met Kristine back in Madison.

They were both teenagers at an alternative high school. Malcolm Shabazz—named

after Malcolm X—which Kristine transferred to when her regular public

school proved too confining. Kristine, the youngest of six Kupka children,

had moved to Madison with her mother (then a factory worker) and several siblings

after the death of their father, a firefighter whom Ellie had divorced. After

rural Mount Carroll, Illinois, the avant-garde atmosphere of Madison, with

its history of academic and political activism, suited Kristine—as did

the ultraprogressive Shabazz school, where students reclined on couches and

did "free writing" exercises. Kristine went on to the University

of Wisconsin, then dropped out.

In her twenties, Kristine made her way to Atlanta. She got a waitress job

and roomed with Kelly Richardson, now a film-production assistant. But Atlanta

was too makeup-and-big-hair; and on a trip to New York, when she visited her

sister Kathy, who was living with Kevin in a tenement on East 3rd Street,

she vowed to move there. When Kathy and Kevin moved out, Kristine moved in.

Her clothes changed from flowing neo-hippie to sleek black-on-black.

She got a job at MacDougals Cafe’., a tourist magnet across from Cafe’

Le Figaro in the Village. Nick Papanikoluóa young Greek-American raised

in Brooklyn, Greece, and the Boston suburbs—also waited tables there

while putting himself through college. He was solemn; she was vivacious. They

went to MOMA on their first date. "She kept touching the paintings,"

Nick recalls. " I said, ‘Kristine, they’ll kick us out!’"

She moved into his apartment on Hudson Street, near the mouth of the Holland

Tunnel. After three years, they broke up—her decision—but remained

best friends. She entered Baruch and, maintaining high grades, won a full

Provost scholarship. She founded the school’s Philosophy Club, setting

up debates on whether organized religion is oppressive, on whether focus on

the Holocaust obscures the evil of slavery, and on the media’s roll in

the death of Princess Diana. She typed papers for blind students.

Kathy and Kristine, working-class sisters, shopped at thrift

stores, cooked at home, got $12 haircuts, and took the subway everywhere—always

competing over who could save more money. Kristineís weakness for Joan

& David shoes almost cost her the honor until she found the house in Kensington

and began filling it with roommates to defray the rent. Ozlem has been there

the longest, and she became the little sister Kristine never had. "I

would knock on her door five times a day," says Ozlem, usually with a

question about a romance. "Kristine would say, --Stop being a drama queen.

Just look at the facts!"

With men, Kristine could give as good as she got. She often chewed them out

for not calling when they said they would. "She didnít want to

dominate, but she was powerful. It was challenging for the man and for her,"

says Ozlem. Kristine put it more bluntly to her friend Suzana Riordan: "You’re

like me. We have balls—we scare ‘em off." She was involved

with a law student, then, for months, a security guard. Lilien says, "I

felt she picked men who weren’t her equal. She’s a really strong

person. She needed somebody who could match her." Her mother, who had

thought the security guard was "an overgrown brat," was pleased

when Kristine stopped seeing him sometime around last winter. At the time,

her mother recalls, "Kristine said, ‘No more men! No more relationships!

I’m going to settle down now and just finish school!"

But in the spring, Kristine started telling people she had a crush on her

science teacher. She told her mother she was attracted to his intellect. Ozlem

recalls her saying that "his skin was so clean and he didn’t drink,

didn’t smoke, never ate meat. She also liked him because he had all these

tacky neckties and not-matching clothes." Valerie Santos, a social worker

who was Negril’s night hostess, says that at first Kristine "didn’t

know how to read him; she was trying to figure out if he had a girlfriend."

Then Kristine told Valerie that Rudy "was single—he had recently

broken up with someone. He basically gave her the impression he was available."

They exchanged numbers—her phone, his beeper. During conversations they

had after class, he told Kristine about a business trip he would soon be taking

to Turkey. An envious Kristine quipped to Kathy, "I wish he could take

an assistant."

Once he filed the class grades, Rudy Persaud drove to Kristine’s house

for a date. He was leaning on a walking stick, Ozlem recalls, the result of

a foot injury. "He made it sound like he wanted a relationship,"

Kathy recalls Kristine later telling her about the day, which had included

lovemaking. But Ozlem had picked up a different vibe. "He’s adorable,"

she said, "but he’s hiding something."

Rudy Persaud’s family is one of the more than 200,000 Hindu families

who have flocked to America from Guyana (overwhelmingly to Queens, especially

Richmond Hill) since the sixties, during and after the unfriendly regime of

Prime Minister Forbes Burnham. They left a Caribbean country where they and

their forebears had lived since coming there as indentured laborers from India

between 1838 and 1917. Queens now has about twenty Hindu temples. Pandits

like Rudy’s father, having witnessed a full generation of Hindu youth

raised on rap music make pleas for traditional morality and spiritual regeneration.

In mid-June, Kristine told Valerie Santos she felt certain she was pregnant;

Valerie brought her a pregnancy test from the health clinic she worked in.

When it came out positive, despite the certainty she’d expressed to Valerie,

"she was shocked," Kathy says. "It took a day for it to settle

in—she hadn’t planned it. But then she said, ‘I’m graduating

in January, I have a great house, I’m already 28--I can do it."

Even though she only had sex with him once, Kristine told friends there was

no question that Persaud was the baby’s father. Still, she was afraid

to tell him, Kathy says, but she did not put the task off. She beeped him,

and when he called her back, she said she had something important to discuss;

could she see him in person? When he said he was busy, she broke the news

on the phone. According to the accounts of several of Kristine’s friends,

he heatedly denied paternity, claiming heíd had a vasectomy (a "partial

vasectomy" was the term Kristine told Kathy and Nick he had used). Then

in a subsequent conversation (again, according to what Kristine told friends),

he backed away from the vasectomy assertion. He stopped denying paternity.

"He started crying—literally crying," Kathy says Kristine told

her. "He started begging her to have an abortion." He told her that

he had gotten married. (Apparently, the Turkish "business trip"

had been his honeymoon, and his new wife was a young Brahmin woman.) "He

said, ‘You’re going to ruin my life! My parents are going to disown

me!’" He said his wife and his parents were going to pay his tuition

to dental school. "‘You can’t do this to me!’ This can’t

happen!’"

Kathy reports, "He talked to her a few more times. Each time, he begged

her again to have an abortion—the baby ‘would ruin his life.’

She was trying to work it through with him. I said, ‘Would you stop already?

It’s his problem! You don’t have to make it right for him.’

But she wanted it to be right for him."

She had reasons for this. She wanted his name on the birth certificate so

her child wouldn’t be embarrassed enrolling for school with a document

that did not list a father. The acknowledgment of paternity would also allow

her to sue him for child support, something Kathy pressed her to consider.

"But Kristine is definitely not about money. Never once did she say,

‘Oh he’s gonna be a dentist one day!’" Kristine would

only consider suing for child support "later," Kathy says, "if

down the road she needed money to safeguard the baby."

During these weeks, in July, of talking with Rudy about the pregnancy, "it

got bad, real bad—very negative—between them," says a Negril

waiter named Sean, who had joined Kristine’s band of confidants. She’d

become so afraid of Rudy’s feelings on the matter, she told Sean and

others, "she only wanted to meet him in a public place. I thought she

was being paranoid; she was very assertive and very together, so I was surprised

when she said that." She confided to Nick several times her fear that

Rudy might "hit her in the stomach" or find some other way to end

the pregnancy. She told Valerie (who was arranging her prenatal care) "words

to the effect of ‘If anything happens to me, he will have probably have

done it.’ It was her gut [feeling] from the beginning. She never told

me he threatened her verbally, but she was anxious and scared—and I don’t

think even she could explain why."

Still, Kristine pressed on. She "wanted Rudy to have some kind of relationship

with the baby," Kathy says Kristine told her. He said," How am I

going to do that? I have a wife! My mom and dad would find out!" She

said, ‘You could do it on a weekend. People have problems when they don’t

have a father—they think they’re worthless. They feel abandoned.’"He

stopped calling. She started beeping. Kelly Richardson pleaded, "Kristine,

is there any way you can have this baby and just . . . completely not involve

him? Put him out of the picture?"

Ozlem picked up the ringing phone one evening in late July. A young woman’s

voice demanded, "Do you know someone named Rudy Persaud? You just called

his beeper." Ozlem said no and hung up the phone. The same thing happened

the next morning, at seven. Ozlem woke Kristine and said, "She called

again; I don’t want to get caught in between." The next time, Kristine

answered the phone. And that is how Kristine entered into an astonishing communication,

over the course of a number of phone calls, with Rudy’s wife, Rochelle.

First Kristine told Rochelle she was merely one of Rudy’s students. The

second or third time Rochelle called, Kristine admitted they’d been involved

but that they no longer were and said there was a reason she was remaining

in touch with him. According to several of Kristine’s friends, every

time Rochelle asked what the reason was, Kristine said, "You’ll

have to ask Rudy." Finally Rochelle asked,"Are you pregnant?"

Kristine admitted she was. As Ozlem listened, Kristine carefully explained

that Rudy had told her he wasn’t married (which was apparently true at

the time of their single sexual encounter). According to Kristine’s reports

to several friends, Rochelle expressed explosive anger toward her husband,

even telling Kristine she didn’t want Rudy—why didn’t Kristine

take him? Kristine said she didn’t want him.

Over the course of these phone calls, "at first, Kristine couldn’t

figure the wife out," Valerie Santos says, "and then she felt more

empathy for the woman." Kristine told Suzana Riordan that she tried to

assure Rochelle (in Suzana’s words): "The pregnancy won’t affect

your life together or any children you have; I don’t want to hurt your

relationship; I just need a few things from him." According to what Kristine

told friends, Rochelle seemed to pour her heart out to Kristine: describing

the wedding (it may have been through Rochelle that Kristine determined the

approximate date), musing about an old boyfriend. (Rochelle Persaud was called

at her office for a response. Told New York was doing an article about Kristine

Kupka’s disappearance, she abruptly said, "I don’’t know

anything about it!" When asked whether she had placed calls to Kristine,

she angrily said, "I cannot talk to you right now! You called my job;

don’t you ever call back!" and hung up.)

By summer’s end, to the relief of Kristine’s friends, Rudy and his

wife had slipped out of her life, which seemed to return to normal. But at

the beginning of October, Rudy was back. His parents were out of town, he

said, and his wife had kicked him out. He was staying with a cousin, Kristine

told friends. One day, he met Kristine on her porch—he was "disheveled,"

she said—and told her he was hungry, that he was waiting for Dunkin’

Donuts to throw out its leftovers. Did she believe him? Her mother says: "She

doubted that he was actually kicked out, but it made her feel bad." Nevertheless,

others say she wanted to help him. "She said they would spend days together

and kind of walk around," Valerie Santos says."That they were affectionate

but not sexual. She encouraged Rudy to get back with his wife."

He was cool toward the pregnancy, Kristine reported to her confidants. It

bothered her that he would pat her head but never touch her stomach. Yet he

also seemed to embrace paternal involvement. According to what Kristine told

friends, he offered to be the birthing coach. And he said he wanted to give

the baby a Hindu name. Still, "she was very confused." Valerie Santos

says, "because Rudy had gone from one extreme to another in a really

short amount of time. She was not listening to her gut anymore, because his

nice behavior had swayed her." Yet she never entirely surrendered her

skepticism.

During the last two weeks before she disappeared, in "every conversation

we had," Nick says, her wariness of Rudy "always came up. She was

afraid of him; she was afraid he was going to get somebody to punch her in

the stomach." Ozlem and Kathy say Kristine discussed such fears with

them too. But she usually concluded that he wouldn’t hurt her because

if something happened to her, it would be too obvious; all fingers would point

to him. The third week in October, Kristine was feeling upbeat. She had $7,000

in her savings account, and she had chosen a birthing center on West 14th

Street. Just before she disappeared, she stopped by to visit with Anthon Grant

at school. They sat together in the student-government office and talked about

her future. "She looked so good pregnant," he remembers ruefully,

"and she seemed so happy."